When Saying Yes Becomes the Ceiling

How chronic yes-saying traps senior ICs, weakens teams, and masks structural debt

The promotion that never comes rarely looks dramatic from the outside.

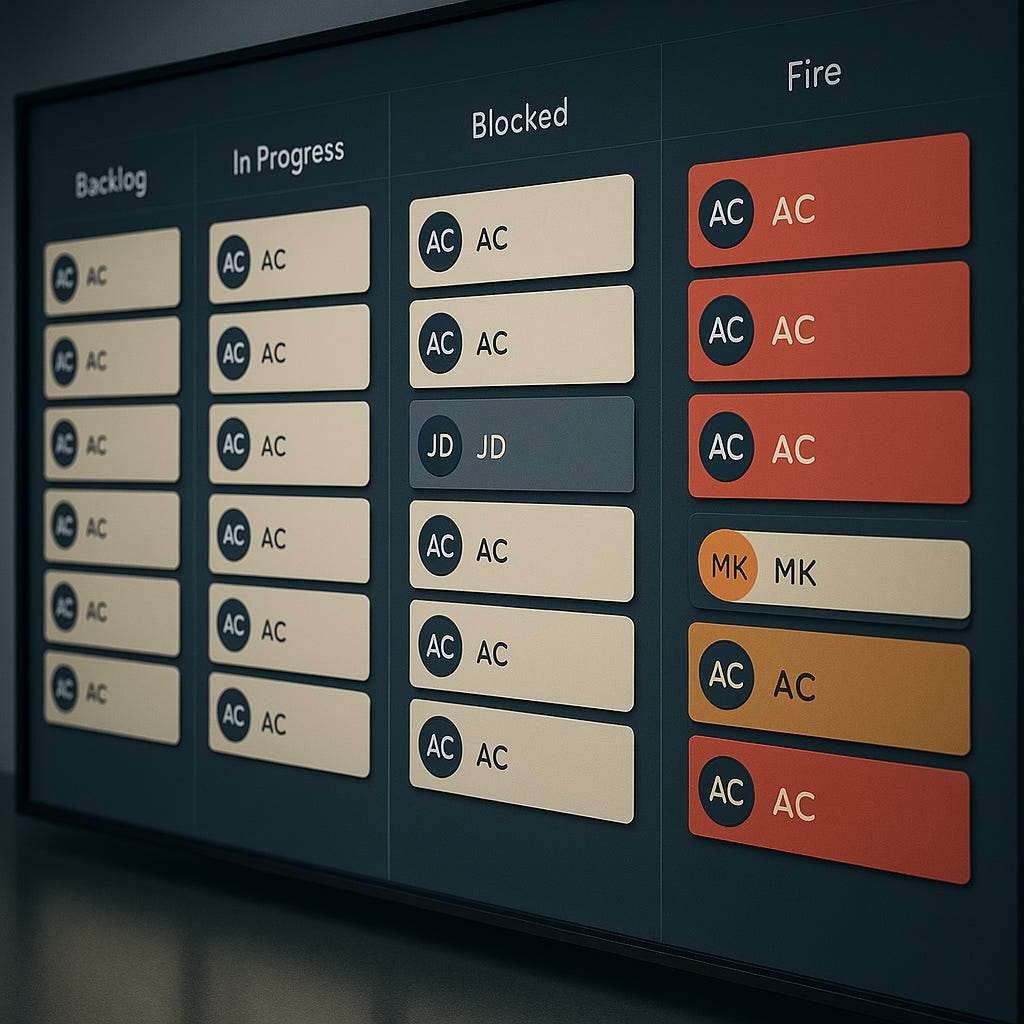

It’s the engineer who says “sure, I can do that” in every planning meeting. The PM who quietly picks up the work nobody signed up for. The ops lead who keeps taking on “just one more” responsibility until they’re effectively doing three jobs. Their calendars are packed, their Slack is on fire, and their names show up in every “thank you” email.

And yet… they’re stuck.

The steady, reliable “can-do” people become the unofficial insurance policy of the company. Early in their career, that label is pure upside. Managers trust them. Leaders remember them. Work finds them. At some point, usually in that band between senior and “should be leading bigger things by now,” the same trait that made them stand out starts to box them in.

When I think back on the people who carried the heaviest load on my teams, I see two distinct patterns that often get blurred. One is the hero. The hero shows up in visible crises. They save the production outage at 2 a.m., pull the all-nighter before the board meeting, personally carry the death-march project over the line. Their stories are loud and retold.

The other pattern is the can-do person. They’re not chasing drama. They are the ones who quietly say “yes” when something ambiguous, messy, or unowned appears. They pick up extra scope without complaint. They catch the dropped balls before anyone sees them hit the ground. Most of their work is invisible glue.

You can be a hero without being can-do: show up only for big, visible saves and keep your distance from the slow, grinding work in between. And you can be deeply can-do without ever being the name in the all-hands story. It’s that second group I worry about most, because they often don’t realize they’re in trouble until the ceiling is right above their head.

Most can-do careers start the same way. Someone throws them into chaos, they figure it out, and people remember. “I can count on you.” At 25, that sentence feels like oxygen. At 35, it starts to feel heavier.

Over time a few things happen.

They say yes on autopilot. Their identity is built on being the one who comes through, so “no” feels like letting the team down, not like focus. They become human routers. Problems get sent their way because everyone knows they’ll either handle it or find someone who will. Their work drifts toward the unplanned and the orphaned. They’re closing gaps and smoothing rough edges instead of shaping the actual system of work.

On paper, their career looks strong. Performance ratings are high. They’re pulled into important conversations. Leaders praise their reliability. If you only looked at feedback forms and kudos channels, you’d assume they’re on a fast path.

The trap shows up somewhere else: in the quiet promotion conversations behind closed doors.

I’ve heard versions of the same sentence in many of those rooms: “They’re amazing, but if they stopped doing X, the whole thing would fall apart.” Or the softer one: “She’s great, but I’d like to see her taking on a bigger scope.” On the surface this sounds like fair feedback. In practice, it ignores the invisible scope that already stretches them across half the organization—the incidents they quietly own, the glue work between teams, the mentoring, the unblocking, the stray responsibilities nobody has written down.

The can-do pattern has trained the company to treat that as background noise rather than real scope. Their current role has quietly expanded far beyond its title, but their next role never seems to show up.

If you zoom out from the individual and look at the team, the picture shifts again. From the outside, a team with one or two strong can-do people looks healthy. Projects land. Incidents get handled. Stakeholders are mostly fine.

If you listen inside the team, you start to hear different phrases.

“Let’s wait for Alex, they know this best.”

“Ask Priya, she always figures this stuff out.”

“Run it by Jordan, they usually take things like this.”

Those aren’t just signs of respect. They are signals of dependency.

People learn a kind of soft helplessness. Instead of wrestling with ambiguous work long enough to understand it, they touch it lightly because they assume the can-do person will step in if things get messy. Skill growth stays shallow. The hardest, muddiest work drifts to the same person every time, and everyone else stays in safer, narrower lanes. The bus factor collapses. You’re one resignation or one medical leave away from a real problem, even if your dashboards and OKRs are all green.

The can-do person often feels like they’re doing the right thing. In their head, they’re supporting the team, helping, unblocking, “just jumping in this once.” What they don’t see is the ceiling they’re building over the team’s capability. The more they quietly absorb, the less anyone else has to stretch.

Healthy teams share pain and context. The scary incidents rotate. The fragile systems are understood by more than two people. People are allowed to struggle long enough to actually grow. None of that happens by accident in a culture that rewards the fastest “I’ll take it.”

There’s a simple test I use with senior folks who suspect they might be in can-do overload: what really happens if you disappear for a month?

Not in the contingency plan you wrote, in reality.

Who panics? Which projects pause or get quietly cut down? Which executives start emailing your manager? Where does your name suddenly appear in status meetings because people are trying to reconstruct what you actually do?

Whatever falls apart in that scenario is a mirror of how you’ve been working.

Now switch chairs and look at this from the manager side. As a manager, nothing feels safer than having a can-do person on the team. When an executive drops a surprise “critical” initiative in your lap, you already know whose name just popped into your head. That instinct is the beginning of the dependency.

You tell yourself you’ll protect them “next quarter,” when things calm down. In the meantime, instead of pushing back on scope or trading work with another team, you slide the new mess toward the can-do person. They say yes, like they always do. The work gets done. You avoid a fight over priorities. You don’t have to bet on someone unproven.

On paper, it works. For a while.

Then you look up and see what you’ve built. One or two high performers are quietly burned out. Their calendar is a wall of “quick syncs,” escalations, and stray responsibilities that don’t match their title. Their growth has stalled because every career-defining project shows up as a late-stage scramble with no room to shape the problem. The rest of the team hasn’t built the muscle to carry heavy, unclear work or to negotiate priorities with stakeholders because someone else always absorbs the chaos. Your group has a reputation as the team that can “always take one more thing,” so other leaders keep piling it on.

No manager writes that down as their operating model. It grows out of a thousand small decisions where the easy answer was “give it to the person who always says yes.”

The harder path for a manager is often the right one. Saying no on behalf of your team even when you know your can-do person could push through. Protecting their calendar for work that changes the system, not just this quarter’s fire. Rotating the hard, messy, politically risky work so other people stretch into it. Being honest in performance conversations: not just “you’re so reliable,” but “you’re the safety net for too many things; that’s not sustainable for you or for us. Let’s spend the next year making sure three other people can carry what only you can carry today.”

That conversation is awkward. It also marks the point where you stop using them as a crutch and start treating them like a future leader.

At company scale, I’ve seen the same pattern in different clothes. In fast-growing or heavily regulated environments, you absolutely need people who can walk into a new domain on Monday, talk to auditors at 9, debug at 10, and explain trade-offs to the board at 11. In the early years, those people keep you alive.

The trouble starts when leadership quietly uses them as a substitute for clear structure and hard trade-offs.

You begin to see chronic priority overload: everything is “critical,” but the same names appear whenever something must be saved. Role gaps become permanent—missing product owners, weak incident management, unclear data ownership—all covered by a few people “who know how things work.” Stories at all-hands center on how “people stepped up” and “teams rallied.” The quiet work of simplifying systems, cleaning up ownership, and removing sources of chaos rarely gets mentioned.

At that point, can-do employees stop being a strength and start being a kind of hidden liability. The company has built part of its operating model on a small set of people always saying yes. That doesn’t show up in the risk register, but it should.

I’ve sat in board meetings where leadership proudly cited “how our people always step up” as proof of a strong culture. Ten years ago, I might have nodded along. Now, I listen for the second half of the sentence. If the same people have been stepping up for years, you don’t just have commitment; you have an unpriced dependency.

So what do you do if you recognize yourself in this?

I wouldn’t tell a can-do person to stop being can-do. That instinct is usually tied to pride in their craft and genuine care for the team. The goal is not to blunt it, but to aim it.

One practical shift is to change “Sure, I’ll take it” into “Yes, if…”. Yes, if something else comes off my plate. Yes, if this comes with the mandate to fix the system that keeps producing this kind of mess. Yes, if we agree who owns this long term and it’s not just me by default.

Another is to make the invisible visible. For a month, track your can-do work. Every incident you step into, every escalation, every surprise ask, every “quick favor,” every extra responsibility you quietly accept. Then sit down with your manager and go through it together. Which of these should exist at all? Which should move to someone else or to another team? Which are things you will keep doing, but only with different conditions next time?

Day to day, there’s a simple habit that changes the arc over time: teach first, fix second. When someone brings you a problem, resist the reflex to grab the keyboard. Ask questions. Pair on the solution. Write down what you both learned. Share it somewhere people can actually find. It feels slower in the moment. Over six or twelve months, it’s the difference between being the only person who can carry the messy work and being the person who quietly raised the bar for everyone.

When you do that long enough, your value starts to shift. You’re no longer defined by how much extra work you can personally absorb. You’re recognized by how much meaningful work the group can handle because of the systems, ownership, and people you’ve grown.

Good companies will notice that shift and support it. Great ones will expect it and design around it. And if your company just keeps handing you more unbounded work, calling it praise, and never changing the system underneath, that’s not a sign that you need to be even more can-do. It’s a data point about where you stand.

"but I’d like to see her taking on a bigger scope." - I’ve been hearing the feedback a bunch! And I’m curious what that actually means in this context.

To me, a bigger scope could mean making more impact by owning problems end-to-end: understanding pain points, aligning with PMs, designers, and engineers to drive a solution through to delivery. It could also mean leveling up the team and org overall - being that glue to helps others grow.

On the other hand, I’ve also seen “bigger scope” interpreted as chasing high-visibility projects - things like performance wins or shipping critical features that generate revenue. But that can also land people in the situation you described in this article, being the go-to person for X, and stuck there.

I’m wondering what's your take on this (maybe a topic for another article!) What are good questions could ask to better understand what “bigger scope” actually means when people say it.

I really like this approach - let's pair, ask questions and document our findings together. I've been doing the first two for a while, and I'm still building the habit of documenting learning.