Is Your Product Idea Worth Building? The WISE Method Tells You in Seconds

Before you waste 6 months building something nobody wants, ask these 4 questions

The board meeting was running long when our CEO turned to me: "Willian, we've got three product initiatives competing for the same engineering resources. Which one do we build?"

I'd been in this spot before—at Rangle helping companies build products, or at my own startup that crashed and burned spectacularly. These days, I start with four questions that have saved me from building expensive failures. Only after these pass do I pull out the market analyses, competitive matrices, and SWOT diagrams. The questions act like a filter—if an idea can't pass them, no amount of strategic framework gymnastics will save it.

The expensive failures taught me more than the successes. At Xpirit, we burned through six months building a "revolutionary" B2B marketplace because we fell in love with the technology. Beautiful architecture, real-time everything, every best practice in the book. Only problem? The businesses we were building for were perfectly happy with phone calls and Excel sheets. We never asked if they wanted to change.

That failure cost me money, time and trust. But it gave me something valuable: an early warning system for ideas that sound good in conference rooms but die in the market.

The Pattern I Kept Seeing

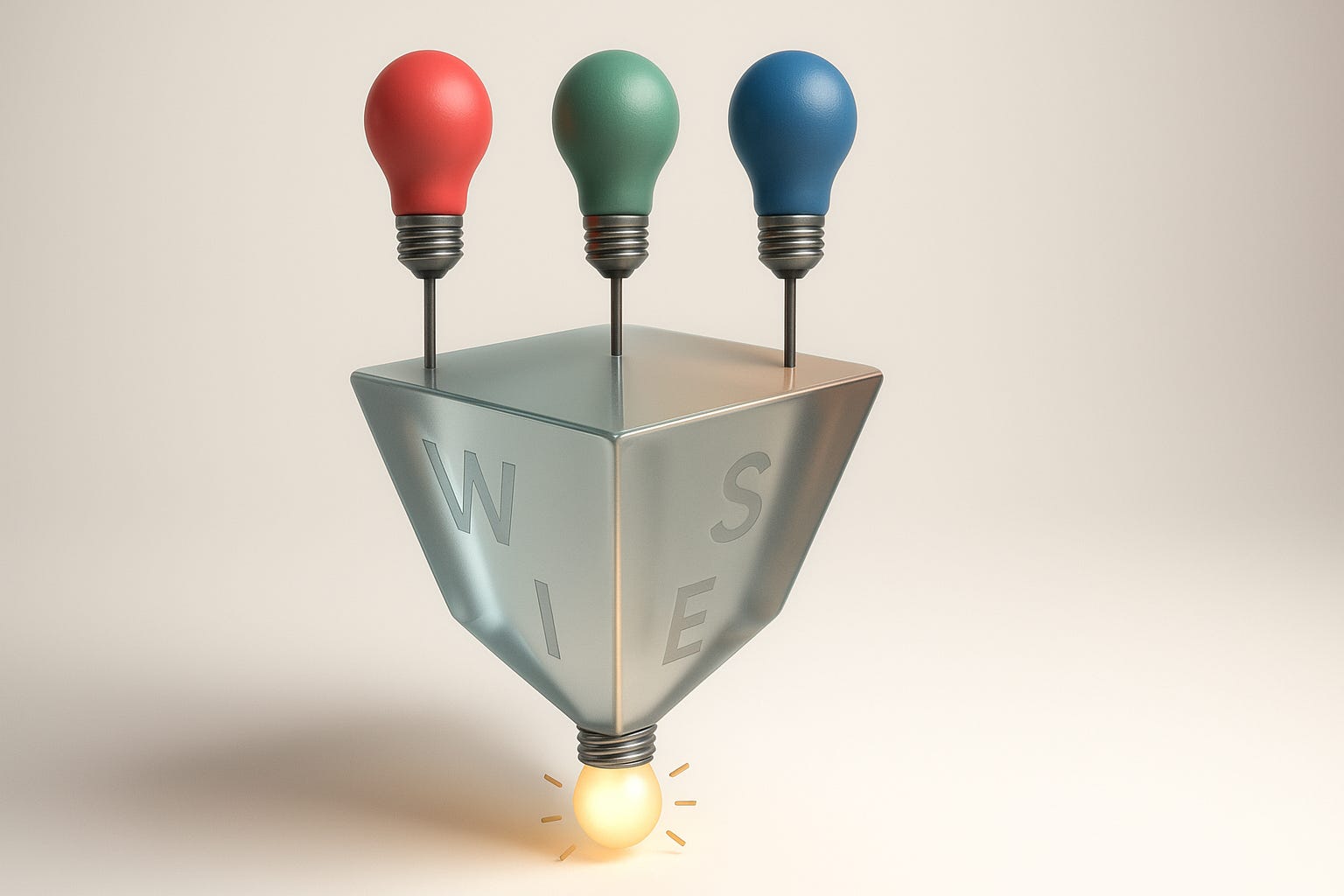

After leading product engineering at companies from 50 to 500 people, I noticed something. The ideas that succeeded weren't necessarily the most innovative or technically impressive. They were the ones that passed what I now call the "WISE Method"—four questions my teams answer before we write a single line of code.

I coined the WISE Method back in 2015, after watching too many companies chase shiny objects. The framework proved its worth during an AI initiative at a company I worked in the past. Everyone was convinced we needed machine learning for personalized recommendations. The investors loved it. The tech team was excited. But when we ran it through WISE, we discovered something interesting: we were solving a problem for maybe 5% of our power users, but it would take 40% of our engineering capacity. Meanwhile, 80% of users just wanted faster page loads and a working search function.

Instead, we built a streamlined search and caching system that cut page load times by 70%. It took six weeks to build and immediately improved retention across our entire user base. The difference? We asked the right questions first.

The WISE Method

W - Words Your Relatives Understand

Can you explain the problem and solution to someone two or three generations removed from you—your teenage cousin or your retired uncle—and have them immediately get why someone would pay for it?

I learned this the hard way at ASTL. We spent months building an "AI-powered business intelligence platform for SMBs." Try explaining that at a family dinner. When we finally talked to actual small business owners, they didn't want AI—they wanted to know if they'd make payroll next month.

The products that work are stupidly simple to explain across any generational or technical divide. Spotify: "All your music on your phone." Square: "Accept credit cards with your phone." If you need slides, statistics, or market education to explain the value, you're already in trouble.

I - In-Use Solutions Today

What are people using today to solve this problem?

This one kills more startups than anything else. If the answer is "nothing," be very suspicious. It usually means the problem doesn't really exist. People are incredibly resourceful—they're already solving their real problems somehow.

When we built the medical app at Rangle, doctors were using WhatsApp to share patient data. Totally insecure, probably illegal, but it worked. We didn't try to create a new behavior—we just made their existing behavior safe and compliant. 50K daily active users across 11 countries proved that approach right.

If they're using something else, you need to be 10x better, not 10% better. And here's the thing most founders miss: 10x better usually means 10x simpler, not 10x more features.

S - Sustainable Economics

At realistic scale (not hockey-stick projections), does the math work?

I've sat through hundreds of pitches with beautiful charts showing exponential growth. "We just need 1% of the market!" Whenever I hear this, I know they haven't done the work. That 1% represents millions of customers choosing you over established competitors—each one a small miracle of market dynamics, timing, and execution.

Here's what I do instead: Take your most pessimistic projection. Cut it in half. Now show me how the business works. Don't hand-wave with "we'll figure it out with volume" or "the data will be valuable." If you can't show a path to profitability at 1/10th your projected scale, you're building on sand.

At a fintech company I worked with, when we evaluated our platform scaling from 120 to 500 transactions per second, we modeled the infrastructure costs at every step. The math worked at 200 TPS. Everything above that was gravy. That discipline saved us from overbuilding and burning cash we didn't have.

E - Effort to Adopt

How much does user behavior need to change for your product to work?

Every additional step—creating accounts, downloading apps, changing workflows—dramatically reduces adoption. This is why I think Quibi was doomed from the start. They required people to change when, where, and how they watched video. That's a massive adoption effort for marginal benefit.

The most successful products I've built slipped into existing behaviors. When we added mobile payments to a retail platform, users didn't need new accounts or apps. They used the same checkout flow, just tapped their phone instead of swiping a card. Adoption was 10x what we projected because we demanded zero behavior change.

The Questions Behind the Questions

These four questions work because they force uncomfortable conversations early. I've watched teams spend months in denial because nobody wanted to admit the idea was flawed. The framework gives permission to be skeptical without being negative.

But here's what took me years to understand: passing all four questions isn't enough. You also need to ask: Do we have the right team to execute this? Are we solving this problem because we're uniquely positioned to, or just because we can?

At Rangle, we had brilliant engineers who could build anything. But when enterprise clients asked for blockchain solutions in 2018, we passed. Not because blockchain was bad (though most use cases were), but because we had no special advantage. Better to be excellent at something that matters than mediocre at something trendy.

What WISE Actually Looks Like

Consider Google Glass. The tech press was mesmerized. Early adopters couldn't wait. Google had the best engineers in the world working on it. But run it through WISE:

Words Your Relatives Understand: "Glasses that... wait, do what exactly? Take pictures? Show emails? Give directions?" No clear singular purpose. Fail.

In-Use Solutions: People were already using smartphones for everything Glass offered. The phone was right there in their pocket. Why wear it on your face?

Sustainable Economics: $1,500 consumer price point for experimental hardware. Manufacturing costs that wouldn't scale down quickly. Developer ecosystem that needed massive investment. The math never worked.

Effort to Adopt: Users had to charge another device, learn voice commands, deal with social stigma, and fundamentally change how they interacted with technology in public. Massive behavioral change required.

The WISE Method would have predicted exactly what happened. Google Glass became a cautionary tale about building technology because you can, not because you should.

But here's where it gets interesting. Sometimes revolutionary products fail WISE initially but still deserve to exist. Take Airbnb. In 2008, it would have failed spectacularly:

Words Your Relatives Understand: "Stay in a stranger's house instead of a hotel?" Your uncle would think you'd lost your mind.

In-Use Solutions: Hotels existed. Nobody was asking for amateur hospitality.

Sustainable Economics: How do you even price insurance for people destroying each other's homes? What's the take rate? Complete unknown.

Effort to Adopt: Massive. Trust strangers. Take photos of your home. Manage bookings. Clean for guests. Huge behavioral change on both sides.

The difference? Airbnb solved a screaming, urgent problem during a specific moment—the 2008 Democratic National Convention when every hotel room in Denver was booked. They found people desperate enough to try something crazy. Then they grew from that beachhead.

The lesson: WISE tells you when you're facing an uphill battle. If you fail all four, you better have a compelling answer to "why now?" and "why us?" Airbnb had both. Google Glass had neither.

Also

What I've learned after 25 years in this business is that ideas which succeed create energy instead of consuming it. The best engineers volunteer for them. Customers ask when they can have it, not why they need it. The math works on a napkin, not just in a spreadsheet.

You know what really tells me an idea is worth pursuing? When I can explain it to another engineering leader and they immediately say, "How has nobody built this yet?" followed quickly by "When can I use it?"

That's what happened with our data privacy platform. The California privacy regulations had created new requirements that everyone was struggling to implement. Our solution was obvious once you saw it: treat user data requests like credit card chargebacks, with real-time processing and transparent controls. Every company who saw our demo wanted it immediately.

No fancy frameworks needed when the problem is that clear and the solution is that obvious. But most ideas aren't that clean, which is why I keep coming back to these four questions.

They've saved me from building products nobody wanted, features nobody would use, and platforms nobody would pay for. More importantly, they've helped me identify and double down on the ideas that actually matter.

Because in the end, the scarcest resource isn't engineering talent or investor money—it's focus. And the WISE Method helps me figure out what deserves it.